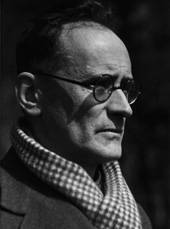

Anton Webern

*3 December 1883

†15 September 1945

Works by Anton Webern

Biography

1883 – Born on 3rd December in Vienna.

1888 – First piano lessons with his mother.

1890 – The Webern family move to Graz.

1894 – The Webern family move to Klagenfurt where Anton Webern attends the Gymnasium focusing on humanities.

1895 – Webern begins his first music lessons.

1899 – Webern writes his first compositions.

1902 – Graduation from Gymnasium in Klagenfurt, trip to Bayreuth, studies at the Vienna University.

1904 – Begins his studies with Arnold Schönberg.

1906 – Doctoral degree for his dissertation; death of his mother, composes the Piano Quintet.

1908 – completes his studies with Schönberg; substitute conductor at the theatre of Bad Ischl; world premiere of Passacaglia op. 1 in Vienna under Webern.

1910 – conducting post in Teplitz; then substitute conductor in Danzig where Passacaglia is performed under Webern.

1911 – On 22nd February Webern marries his cousin Wilhelmine Mörtl; His Tochter Amalia is born; then a one-year stay in Berlin.

1912 – Conductor in Stettin; his compositions are first published in the ‚Blauen Reiter’ and the magazine ‘Der Ruf’.

1913 – Settles in Vienna; scandal at the world premiere of Six pieces for large orchestra op. 6 in Vienna; his daughter Maria is born.

1915 – his son Peter is born; Webern serves in the army as a one-year volunteer.

1917 – Released from military service; conducting post at the ‚Deutsche Theater’ in Prague.

1918 – Settles in Mödling; helps to run the Society for Private Musical Performance.

1919 – his daugther Christine is born; death of his father Carl von Webern.

1920 – conducting post in Prague; Universal Edition takes him under contract.

1921 – Conductor of the Wiener Schubert-Bundes, takes charge of the Mödlinger Männergesangvereins.

1922 – Webern conducts his Passacaglia at the ‘Düsseldorfer Tonkünstlerfest’.

Five movements for string quartet op. 5 is performed at the International Chamber Music Festival in Salzburg; takes charge of the Vienna Workers’ Symphony; Conductor of the ‚Freien Typographia’ in Vienna.

1923 – Guest concert under Webern in Berlin; conducts the ‚Wiener Arbeiter-Singvereins’ of the ‚Sozialdemokratischen Bildungsstelle’; Schönberg introduces his students into twelve-tone music.

1924 – World premiere of Six bagatelles for string quartet op. 9 and Six Lieder for voice, clarinet, bass clarinet, violin and cello op. 14 in Donaueschingen; Great Music Prize of the City of Vienna.

1925 – Teacher at the ‚Wiener Jüdischen Blindeninstitut’.

1926 – Webern leaves the Mödlinger Männergesangverein; Meets the couple Jone-Humplik.

1927 – Conductor of the Austrian Broadcasting Corporation.

1928 – Composes Symphony op. 21; Webern suffers from stomach ulcers; Commission from the ‘League of Composers’.

1929 – Concerts in Frankfurt and London with Webern’s co-operation.

1930 – Adviser, lector und censor at the Wiener Rundfunk.

1931 – Concerts in London; Music Prize of the Municipality of Vienna.

1932 – Concerts in London and Barcelona; move to Vienna, then to Maria-Enzersdorf.

1933 – Concert in London; celebrates his 50th birthday in Vienna.

1934 – Dollfuß coup; ban of social democratic party, Webern resigns from his position in the ‘Kunststelle’.

1935 – Concert in London; Alban Berg dies.

1936 – Webern resigns as conductor at the IGNM Festival in Barcelona; Concert in Winterthur conducted by Webern.

1938 – Commission from Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge for a String quartet; World premiere of the cantata Das Augenlicht in London.

1940 – Trip to Switzerland.

1943 – Last trip abroad to Switzerland; Webern turns 60 years.

1945 – Peter Webern dies on 11th February; the Webern family flee to Mittersill;

Anton Webern is mistakenly shot on 15th September by an American soldier.

About the music

„It is obvious that Webern – who emerged very early on as the chief landmark in defining our own personalities – stands at the centre of these ‚explorations’. There are innumerable commentaries on Webern, but they are only useful inasmuch as they have isolated the lines of force active at the present time: the consideration of the series as a hierarchic distribution, the importance of the interval and of intervallic proportions, the role of chromaticism and of complementary sounds, and the assembling of structures from the different characteristics of the sound phenomenon.”

In the quote above, published in his Penser la Musique Aujourd’hui in 1963, Pierre Boulez reflects on how young composers who came to maturity after World War II turned to Anton Webern as THE pivotal figure of the pre-war “avant-garde” (more than Schoenberg or Berg and certainly far more than Stravinsky or Bartók) and why they did so.

No-one could have put it more succinctly and with more justification than Boulez: “Webern, the chief landmark in defining our own personalities…”

In 1957, twelve years after the war, when Kurtág arrived in Paris, he copied half of Webern’s scores because they were not available in Hungary – and in copying them, and analysing them, drew important conclusions for his own subsequent work. For Kurtág, Webern is, and has always been, music at its purest.

It is a tragic moment in music history that Anton Webern should have been killed accidentally a few months after the war, in 1945, just as he was about to be taken up by a new generation of young composers. He would at last have come into his own, would have tasted the success that had evaded him during his lifetime – his music was simply too austere, too uncompromising, too radically new in its utter reduction of means and time scale to have found favour with audiences.

After the Anschluss, his music was suppressed, and had it not been for Alfred Schlee, who stayed with Universal Edition after its “aryanization” by the Nazis, he would have had no income whatsoever. Schlee saw to it that Webern was regularly supplied with work – proof-reading and the like – which allowed him to make ends meet.

In fact, the Second Viennese School as a whole has a tragic side to its history: the founder-teacher, Arnold Schönberg, was forced to emigrate to the United States and start life anew in late middle-age, living to see first Alban Berg die at fifty in 1935, and then Anton Webern ten years later. A terrible loss for him as a teacher-turned-friend, and a terrible loss for music history.

By the time Anton Webern decided to study with Schönberg, in 1904, he had already composed a great deal, including the orchestral work Im Sommerwind, which is still heard now and then in concerts. His creative impulse was offset by self-doubt and also the doubt expressed by his father as to his talent: Anton was supposed to study farming and take over the family property.

Instead, he studied musicology at university, obtaining his doctorate with a thesis on Heinrich Isaac; he also studied art history, joined the Albrecht Dürer Society, and visited galleries in Munich and Salzburg in the early years of the 20th century when exciting new movements were emerging in painting, including The Blue Rider in Munich and The Bridge in Dresden.

Amazingly enough, Webern’s knowledge of music history surpassed – thanks to his university education – that of his teacher. Apparently, Schönberg’s interest in the subject was limited to what came useful for his own compositional work, and was inspired by his pupil (who wished to place every work they analysed in class in its historical perspective) to devote himself to music historical studies.

Emil Hertzka, the Director of Universal Edition, that incomparable discoverer and mentor of new musical talent, approached Webern as early as 1914 – that is, just five years after concluding contracts with Mahler and Schönberg and before contacting Bartók or Janácek, not to speak of Berg – but World War I prevented ties from being finalised. That is why Webern only joined the UE’s stable of composers in 1920, the same year as Kodály and three years ahead of Berg.

To jump ahead once again: whereas we owe it to Emil Hertzka that Anton Webern found a publisher for his compositions (previously, some of his pieces had appeared at his own cost), it was another UE figure, Alfred Schlee, who saved the plates of Schönberg’s, Berg’s and Webern’s compositions during the war. He knew they were in danger of being destroyed, so he buried them in his garden, ensuring a rapid revival of the Second Viennese School when the war was over.

It is difficult to imagine a closer symbiosis between a composer and a publisher than the one that developed over the decades between Anton Webern, his teacher, his fellow pupil and Universal Edition. Theirs is a unique success story – of three distinct creative personalities, who had a very hard time having their music accepted, and who nevertheless made it, in their lifetimes or posthumously, thanks to the unwavering support of their publisher.