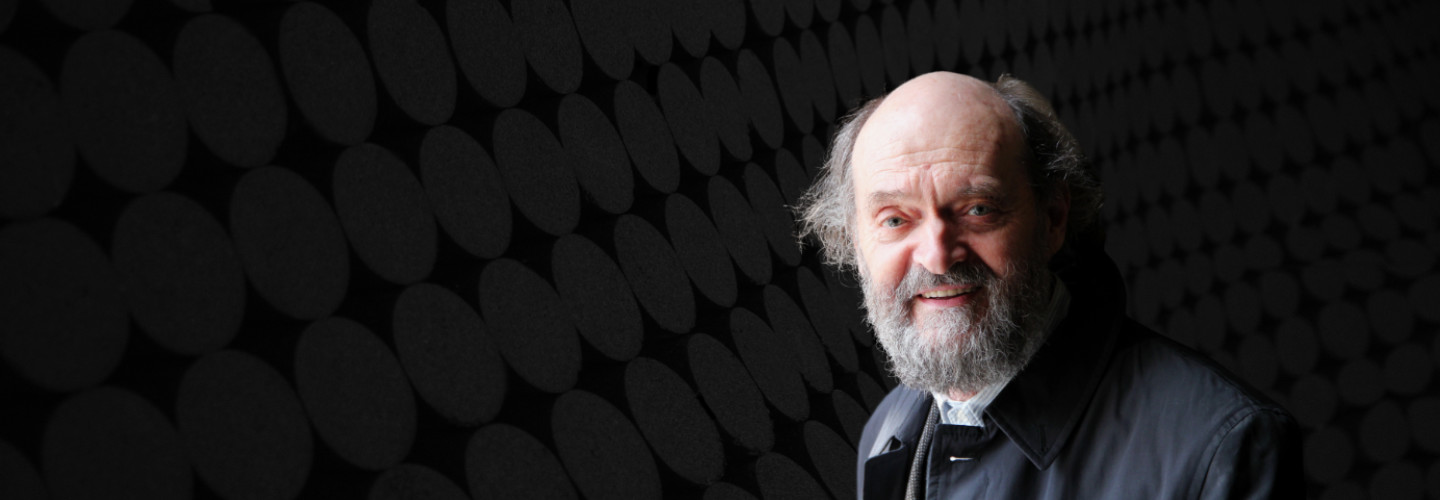

Arvo Pärt

*11 September 1935

Works by Arvo Pärt

Biography

Arvo Pärt was born in 1935 in Paide, Estonia. After studies with Heino Eller’s composition class in Tallinn, he worked from 1958 to 1967 as a sound engineer for Estonian Radio. In 1980 he emigrated with his family to Vienna and then, one year later, travelled on a DAAD scholarship to Berlin.

As one of the most radical representatives of the so-called ‘Soviet Avant-garde’, Pärt’s work passed through a profound evolutionary process. His first creative period began with neo-classical piano music. Then followed ten years in which he made his own individual use of the most important compositional techniques of the avant-garde: dodecaphony, composition with sound masses, aleatoricism, collage technique. Nekrolog (1960), the first piece of dodecaphonic music written in Estonia, and Perpetuum mobile (1963) gained the composer his first recognition by the West. In his collage works ‘avant-garde’ and ‘early’ music confront each other boldly and irreconcilably, a confrontation which attains its most extreme expression in his last collage piece Credo (1968). But by this time all the compositional devices Pärt had employed to date had lost all their former fascination and begun to seem pointless to him. The search for his own voice drove him into a withdrawal from creative work lasting nearly eight years, during which he engaged with the study of Gregorian Chant, the Notre Dame school and classical vocal polyphony.

In 1976 music emerged from this silence – the little piano piece Für Alina. It is obvious that with this work Pärt had discovered his own path. The new compositional principle used here for the first time, which he called tintinnabuli (Latin for ‘little bells’), has defined his work right up to today. The ‘tintinnabuli principle’ does not strive towards a progressive increase in complexity, but rather towards an extreme reduction of sound materials and a limitation to the essential.

Creative Periods

I. 1958-1968

Neoclassicism – Avant-garde

As befits one of the most radical exponents of the so-called Soviet Avant-garde, Pärt’s oeuvre bears witness to the composer’s own deep-reaching musical evolution. His first period of creativity began with neo-classicist piano music (Two Sonatinas op. 1 and Partita op. 2), with the next ten years being given over to the most important compositional techniques of the avant-garde – twelve tone serialism, sonic fields, indeterminism, collage technique – all of which saw highly original use in his music.

Nekrolog (1960) was the young composer’s first important work and, at the same time, the first twelve-tone work of Estonian provenance. It was both his first success and his first scandal, provoking official accusations of “western decadence”.

Perpetuum Mobile (1963) is one single, pulsing, powerful wave of sound, which is constructed from variously pulsating individual parts. The piece is characterized by its serial structure, which is reduced to radically simple formulae. Both works, Nekrolog and Perpetuum Mobile, garnered the composer initial recognition in the West.

Symphony No. 1 (1963) – the composition with which he earned his diploma. Arvo Pärt left the academy as an experienced and mature composer.

Collage Technique

Collage sur B-A-C-H (1964). Pro et Contra, Symphony Nr. 2 (1966). The composer’s further stylistic development led him to experiment with collage technique. In the works of this period, Pärt juxtaposed two highly discrepant ideas of sound: avant-garde passages alternate with direct quotations or imitations of earlier musical styles. His own music suddenly took on the nature of arena, playing host to battles between the stylistic means of modernity (Pärt’s music) and the simple, transcendental beauty on which he had set his sights (the musical quotations). New and old music stood opposite one another, irreconcilably at odds. This sort of confrontation experienced its ultimate, unsurpassed climax in his last collage work, Credo.

Credo (1968). With this work, in which the composer took on Bach’s Prelude in C Major (WTC 1), Pärt intensified and hardened his musical language to an extreme degree – “an amassment of violent power, straining at its own limits like an avalanche” (Part). This battle between the two musical worlds is concluded by Bach’s victory over the modernistic cataclysms in Pärt’s own music.

II. 1968 to the present

Crisis: 1968-1976

The 'triumph' of the musical quotations in Credo marked a decisive turning-point in Pärt’s development. From that point on, he regarded all his previous compositional techniques as meaningless. Pärt’s quest for his own musical voice drove him into a creative crisis that dragged on for eight years, with the composer unable to predict when he might once again emerge. During this period, Pärt had to “learn how to walk all over again” (Pärt). In the wake of this artistic turning point, Pärt withdrew completely and stopped composing. In search of a new musical language, he studied Gregorian chant, the Notre Dame School and classic vocal polyphony. Pärt’s intensive study of these eras was essential to his new outlook on music, a fact best illustrated by his statement that “…hidden behind the art of connecting two or three notes lies a cosmic mystery.” The composer’s eight years of silence were steeped in the intense desire to comprehend precisely this. Pärt’s long silence was broken only by the Symphony No. 3 (1971), his sole authorized transitional work from this period.

1976: Tintinnabuli

In 1976, the long silence finally gave birth to music – to the piano miniature Für Alina. It is clear that, with this piece, Pärt had found himself, and the compositional technique he used then for the first time inspires his oeuvre to this day. The technique, upon which Pärt has bestowed the name Tintinnabuli (Latin for 'little bells'), is achieved not through a progressive increase in complexity, but much rather results from an extreme reduction of the sonic material and from the discipline of limiting oneself solely to that which is essential.

The Tintinnabuli technique of composition is a process by which a form of polyphony is built out of tonal material drawn from beyond the paradigms of functional harmony. In vocal works, structure and form are additionally subject to all parameters of the text (syllables, words, accents, grammar, punctuation).

At the style’s core lies a 'duality', a new sort of 'basic structure': two parts join to form an inseparable whole. One of the two is the omnipresent major/minor triad, the notes of which are bound to the other – the so-called 'melodic voice' – by strict rules. This 'duality' of two juxtaposed parts, which exist only in connection with one another, joins to form the smallest and most important building block of the Tintinnabuli style.

The combination of this compositional style’s formal logic and its starkly reduced sonic material inevitably results in an extremely dense musical texture. The focus on the basic musical unit remains Pärt’s foremost concern. Thanks to his ascetic compositional approach, his music leaves the listener with an impression of concentration and objectivity. "Music,” says Pärt, “must exist in and of itself … the mystery must be present, independent of any particular instrument … the highest value of music lies beyond its mere tone colour.” This, the composer’s aesthetic credo, has resulted in many hitherto unusual performance practice characteristics. A case in point is the work Fratres. It was originally composed as music in three parts – without, however, being connected to any specific tone colour. Consequently, Fratres can play host to various constellations of tone colours, a fact which has led to versions for various types of ensembles.

The birth of the Tintinnabuli style is rooted firmly in the history of European music. One might view this style as a synthesis of old and new, with classic vocal polyphony on the one hand and serial music on the other. Far from copying either style, the composer has internalized the essences of both and combined them with his compositional technique, which one might call a sort of 'new austerity' (quite literally: 'punctus contra punctum'). The result is an extremely individual world of sound marked by both the impersonal and the personal, by both discipline and subjectivity.

By now, there have been several attempts to label the Tintinnabuli style such as “new simplicity”, “minimal music”, etc. Tintinnabuli is a new phenomenon which is difficult to analyse and classify by way of existing musicological standards. With his compositions, Pärt has brought about a paradigm-shift in modern music, and the attempt to analyse this shift has in turn given rise to its own process of creative discovery.

Nora Pärt, Saale Kareda

* The Credo scandal – At the time of its première, Pärt’s open affirmation of his Christian faith (the sung text 'Credo in Jesum Christum') amounted to an additional political provocation, and it was viewed as an attack on the regime. This scandal was part of the wild, incessant back-and-forth between approval and outright rejection, which had begun with Nekrolog in 1960 and finally culminated in Pärt’s emigration: in 1980, Estonia’s communist government encouraged him to leave the country.

1935 – Born on 11 September in Paide, Estonia.

1938 – Moved with his mother to Rakvere, Estonia.

1945–53 – Rakvere Music School, piano studies with Ille Martin; first attempts at composition.

1950–54 – Rakvere High School.

1954 – Tallinn Music School, composition studies with Harri Otsa.

1954–56 – Military service at Soviet Army, playing oboe, percussion and piano in the Military Band.

1956 – Continuation of studies at music school, now with Veljo Tormis.

1957–63 – Tallinn Conservatory, composition studies with Heino Eller.

1958–67 – Sound Engineer at Estonian Radio.

Since 1967 – Freelance composer.

1958-68 – First creative period starting with neo-classicist piano music; experiments with serial techniques, aleatoricism, collage and sonic fields. Works like Nekrolog (1960), Perpetuum mobile (1963), Collage sur B-A-C-H (1964), two symphonies (1963 and 1966), Pro et contra (1966).

1968 – Credo, conclusion of his first creative period. In this work the confrontation between two musical worlds – Bach’s Prelude in C Major (WTC 1) and Pärt’s own dodecaphonic music attains its most dramatic expression. An open affirmation of Christian faith caused a scandal in Soviet Estonia and the piece immediately became banned.

1968-76 – New artistic reorientation. In search of a new musical language, he studied Gregorian chant, the Notre Dame School and renaissance polyphony. Pärt’s long silence was broken only by the Symphony No. 3 (1971), his sole authorized transitional work from this period.

1976 – Für Alina is the first composition in tintinnabuli-technique (tintinnabulum – Latin for ‘little bell’), which inspires his oeuvre to this day. The musical material of Pärt’s works is extremely concentrated, reduced to the essential.

1976–77 – 15 tintinnabuli-compositions, including Tabula rasa, Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten, Fratres, Summa.

Première of Tabula rasa in Tallinn, September 30, 1977 by Gidon Kremer (violin), Tatiana Grindenko (violin), Alfred Schnittke (piano), Tallinn Chamber Orchestra and conductor Eri Klas.

1980 – Emigration to Vienna; contract with the publisher Universal Edition.

1981 – Grant from the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), moving to Berlin.

1982 – Passio, commissioned by Bavarian Radio and premièred in Munich by the Bavarian Radio Choir, soloists, instrumental ensemble and organ, conductor Gordon Kember.

1984 – Beginning of the creative collaboration with the CD label ECM and producer Manfred Eicher. Release of the CD “Tabula rasa”, which launched a whole new series of recordings under the title ECM New Series. Since then all authorised first recordings of major works with ECM.

1985 – Stabat Mater, commissioned by Alban Berg Foundation and premièred in Vienna by the Hilliard Ensemble, Gidon Kremer (violin), Nabuko Imai (viola) and David Geringas (violoncello).

Te Deum, premièred in Cologne by the Kölner Rundfunkchor, Kölner RSO and conductor Dennis Russell Davies.

1989 – Miserere, commissioned by and premièred at Festival d’Eté de Seine-Maritime, Rouen, by Hilliard Ensemble, The Western Wind Chamber Choir and Instrumental Ensemble, conductor Paul Hillier.

1989-2011 – Eight Grammy nominations mostly for the best contemporary composition.

1990 – Berliner Messe, commissioned by 90. Deutschen Katolikentages Berlin and premièred in Berlin by Theatre of Voices and conductor Paul Hillier.

1991 – Honorary membership of Royal Swedish Academy of Music, Stockholm.

Silouans Song, commissioned by Svenska Rikskonserter and premièred in Rättvik, Sweden by Chamber Orchestra of the festival Music at Lake Siljan and conductor Karl-Ove Mannberg.

1994 – Litany, premièred in Eugene, USA, by the Hilliard Ensemble, Oregon Bach Festival Chorus and Orchestra, conductor Helmut Rilling.

1996 – Honorary membership of American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York.

Dopo la vittoria, commissioned by the City of Milan in commemoration of the 1600th anniversary of the death of Saint Ambrose and premièred in Milano in 1997 by Swedish Radio Choir and conductor Tõnu Kaljuste.

1997 – Kanon Pokajanen, composed for Cologne Cathedral’s 750-year anniversary, premièred in 1998 in Cologne Cathedral by Tõnu Kaljuste and the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir.

1998 – Como cierva sedienta, commissioned by and premièred at the Festival de Música de Canarias in 1999, by Patricia Rozario, Copenhagen Philharmonic Orchestra and conductor Okko Kamu.

1999 – Cantique des degrés, commissioned by the Princess of Hanover for the 50th anniversary of the coronation of Rainier III, Prince of Monaco; premièred in Monaco Cathedral by Monte Carlo Opera Choir, Monte Carlo Philharmonic Orchestra and conductor Tõnu Kaljuste.

2000 – Cecilia, vergine romana, commissioned by Agenzia Romana for the events of Holy Year 2000; premièred in Auditorium Roma by the Choir and Orchestra of the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, conductor Myung-Whun Chung.

Receives the Herder Prize, Germany.

2002 – Lamentate, for piano and orchestra, subtitled Homage to Anish Kapoor and his sculpture ‘Marsyas’, premièred in 2003 in London, in the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall by Hélène Grimaud, London Sinfonietta and conductor Alexander Briger.

2003 – Classic Brit Award – Contemporary Music Award for Orient [&] Occident.

In principio, commissioned by Diocese Graz-Seckau for the program “Graz 2003 – Culture Capital of Europe” and premièred by choir pro musica graz and Capella Istropolitana, conductor Michael Fendre.

2004 – Da pacem Domine, a cappella work commissioned by Jordi Savall. In 2007 a recording of the piece (in collaboration with Estonian Philharmonic Choir and conductor Paul Hillier; Harmonia Mundi) wins Grammy Award as best choral recording.

L’abbé Agathon, commissioned by l’Association l’Octuor de Violoncelles / Rencontres d’Ensembles de Violoncelles de Beauvais and premièred in Beauvais by Barbara Hendricks and Beauvais Cello Octet.

2005 – La Sindone, commissioned by Festival Torino Settembre Musica for the Olympic Winter Games 2006 in Turin and premièred in Turin Cathedral by Estonian National Symphony Orchestra and conductor Olari Elts.

Composer of the Year, Musical America, USA.

2007 – Nominated for Grammy Award for Da Pacem CD (Harmonia Mundi).

2008 – Receives the Léonie Sonning Music Prize, Denmark, and composes These words…, commissioned by Léonie Sonning Music Fond and premièred by Danish National Radio SO and conductor Tõnu Kaljuste in Copenhagen.

Symphony No. 4, ‘Los Angeles’, premièred in 2009 by Esa-Pekka Salonen and the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Walt Disney Concert Hall, USA. The work receives its UK première at the BBC Proms in 2010.

Stabat Mater, new version for mixed choir and string orchestra, commissioned by Tonkünstler-Orchester Niederösterreich; premièred in Musikverein, Vienna, by Tonkünstler Orchester and Wiener Singverein, conductor Kristjan Järvi.

2010 – Adam’s Lament, commissioned by Cultural Capital Istanbul 2010 and Cultural Capital Tallinn 2011, premièred in Hagia Irene, Istanbul by Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, Vox Clamantis, Borusan Istanbul Philharmonic Orchestra and conductor Tõnu Kaljuste.

The Arvo Pärt Centre is established in Laulasmaa, Estonia, which holds composer’s personal archive.

Celebrations of Pärt’s 75th birthday include three international conferences: „Arvo Pärt and Contemporary Spirituality Conference” at Boston University, „Arvo Pärt: Soundtrack of an Age” at London’s Southbank Centre and „The Cultural Roots of Arvo Pärt’s Music” in The Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre, Tallinn.

2011 – Returns to Estonia where he resides today.

Classic Brit Award – Composer of the Year for Symphony No. 4.

Honorary Doctorate of the Pontifical Institute for Sacred Music, Vatican.

Is elected first ever Academician for Music by the Estonian Academy of Sciences.

Member of the Pontifical Council for Culture, Vatican.

2012 – BBC’s one-day festival „Total Immersion” in London, dedicated to the music of Arvo Pärt.

Estonian Music Council Composition Award.

Prize of the International Festival Cervantino, Mexico.

Honorary Doctorate of University of Lugano, Faculty of Theology, Switzerland.

2013 – Special program of concerts dedicated to the music of Arvo Pärt held in Schleswig-Holstein Music Festival, August 9.–11. Kanon pokajanen, Te Deum, Adam’s Lament, Tabula rasa and Symphony No. 3 were performed among others.

During the 2013/2014 academic year, professor of Fine Arts at the University of Tartu. Lectures on Arvo Pärt are given by Professor Toomas Siitan (Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre).

2014 – Swansong, new version of Littlemore Tractus for orchestra, commissioned by and to be premièred in Mozart Woche 2014, January 29, Salzburg, by Wiener Philharmoniker and conductor Marc Minkowski.

Nominated for Grammy Award for Adam’s Lament (ECM)

2015 – Awarded the Cross of Merit First Class from the EELC

2016 – Greater Antiphons premièred by Gustavo Dudamel and the Los Angeles Philharmonic

2017 – awarded the Cultural Merit Order of Romania; awarded the Ratzinger Prize

2018 - Gloria-Aris Medal, Poland's highest cultural award for cultural merit

2018 - Publication of a graphic novel by Estonian graphic artist and cartoonist Jonas Sildre (published in German in 2021) "Zwischen zwei Tönen. From the life of Arvo Pärt."

2018 - Opening of the Arvo Pärt Centre in Laulasmaa (Estonia) on 13 October

2019 - German Music Author Award in the choral music category

2020 - BBVA Foundation Frontier of Knowedge Awards in the Music/Opera category

2021 - Grand Cross of Merit of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

2023 - Polar Music Prize (Swedish music prize)

Timeline courtesy of the Arvo Pärt Centre

Visit our #ArvoPart80 blog.

About the music

For the Performer

The confrontation with Pärt’s music can be compared to making an oath of disclosure. Pärt himself says of his compositional point of departure, “It’s enough to play just one note beautifully,” and this applies doubly to interpretation. Here “playing beautifully” means nothing less than 'perfectly'. Thus those whose first encounter with Pärt’s music is based on its disarmingly simple notation will find themselves confronted with much they have not yet mastered. Suddenly, the regularity of up and down strokes, control of vibrato, changes in bowing or strings, and other aspects become fundamental problems.

Pärt’s music does not call for virtuosity behind which one can hide shortcomings in technique or musicality – no exaggerated use of vibrato can replace precise intonation based on the mathematical regularities of the overtone system, or cover up the resulting irregularities. No standarized 'espressivo' can replace the feeling of veracity and responsibility which the performer must develop – here and now – for each and every note. The picture of Saint Christopher comes to mind, who applied his intelligence and strength to much more difficult tasks than carrying a small child across a river – a task at which he almost failed ... Interpreting the 18-minute-long 'Silentium', the second movement of Tabula rasa, for example, is an experience no performer can easily forget: eighteen minutes of quiet notes of differing lengths, consisting only of seven different pitches within the aeolian mode based on D – all this without a single change in tempo, volume or character can only lead the performer into heaven or despair ... It is just such an experience that is usually ignored in regular musical circumstances (including training!), in which we stand naked as before our Creator ...

If we are not scared away by such exposure, then the confrontation with Arvo Pärt can even cleanse our approach to music in general: a scale is suddenly no longer something to be taken for granted, it becomes a conscious experience of climbing and falling; and the faded supermarket and pop triad suddenly becomes a dome of sound, in which three individual notes completely abandon their individuality in favor of a higher order. The medieval or Renaissance musician may have harbored a natural awe for these phenomena – for the listener today, it is nothing less than the rediscovery of them. Finally, what could be more beautiful for a performer than to enrich his own ability to listen and experience music by virtue of his own efforts?

Andreas Peer Kähler, Berlin (1995)

Translation: Robert Lindell