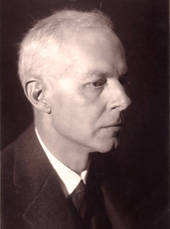

Béla Bartók

*25 March 1881

†26 September 1945

Works by Béla Bartók

Biography

1881 – 25th March: Béla Bartók is born near the Hungarian city of Nagyszentmiklós (today: Sânnicolau Mare/Rumania) as the son of the headmaster of an agricultural school and a schoolmistress

1889 – after his father’s early death his mother brings him up and gives him piano lessons

1893 – music and composition lessons in Preßburg

1899–1903 – after graduating from the Gymnasium he studies composition and piano at the Budapest Academy of Music

1904 – world premiere of his symphonic poem Kossuth in Manchester

1905 – composes Rhapsody for piano and orchestra, the first of Bartók’s works which will be published. His early works are characterized by Hungarian nationalism. He promotes the recognition of the Hungarian peasant song as an idiosyncratic folk art and defines its individual peculiarity as opposed to the music in the city. Bartók’s interest in Eastern European folk music influences his compositions

1908 – composes his first string quartet

1908–1934 – Professor of piano at the Academy in Budapest

1908/09 – publishes a collection of piano pieces based on Hungarian and Slovakian folks songs under the title For children

1911 – composes the piano piece Allegro barbaro and the opera Bluebeard’s Castle

1913 – trip to the oasis of Biskra to study Arab music

1914–1919 – composes the ballets The Wooden Prince (1914-1916), Budapest (1917) and The Miraculous Mandarin (1918/19)

1923 – First world success with Dance Suite for orchestra

1924 – Publication of scientific paper The Hungarian folk song

1934 – Publication of the scientific paper The folk music of Magyars and the neighbouring peoples;

Bartók asks for release from teaching assignment in order to be able to fully focus on research activities

1936 – composes Music for strings, percussion and celesta for the Basel chamber orchestra

1939 – composes Divertimento for string orchestra

1940 – emigration into USA;

appointment as honorary doctor of the Columbia University. Bartók gets a research assignment

1943 – After a break of three years from composing the Concerto for Orchestra is completed

1945 – 26th September: Béla Bartók dies in New York

About the music

It is sheer coincidence that Béla Bartók has become the Hungarian composer we all know. After the early death of his father, who had been director of a small school at Nagyszentmiklós (now in Romania), his mother had to look after her two children (Béla had a sister, Elza) all by herself. The family lived in various towns in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy – such as Pressburg (Pozsony for Hungarians, Bratislava for Slovaks). Lying as it does much nearer to Vienna than to Budapest, it would have been logical for the talented young musician to continue his studies at the prestigious music academy of the imperial capital.

That Bartók and his mother opted for Budapest was due to the influence of Bartók’s friend, Ernö (Ernst) von Dohnányi: four years his senior, Dohnányi was born in Pressburg but decided in favour of the Franz Liszt Music Academy in Budapest where his teachers included the pianist István Thomán (a pupil of Liszt’s) and Hans Koessler, who taught him composition. Bartók was to follow his friend’s example in his choice of professors as well.

The move to Budapest led to an encounter which was to become of fundamental significance for Bartók: he met Zoltán Kodály, who exerted a lasting influence on his development. The two of them became close friends and Bartók would regularly turn to Kodály – whom he regarded as more mature, wiser and more cultured than himself – for advice.

The early years of the 20th century saw an upsurge of national sentiment in Hungary (no wonder that one of Bartók’s first orchestral compositions was dedicated to the memory of Lajos Kossuth, the leader of the Hungarian uprising of 1848/1849) and for a time, the young composer donned a national costume as an outward sign of his patriotism.

More important was the realisation he shared with Kodály that Hungarian art music had reached an impasse. They saw the only way out in collecting genuine folk music, subjecting it to scientific examination with the goal of creating new art music based on it.

They were following the example of Béla Vikár (1859–1945) who as early as 1896 had set out to collect folksongs and was probably the first person in Europe to record them on phonograph cylinders. Vikár was the pioneer; Bartók and Kodály were the founders of ethnomusicology as a scientific discipline in Hungary.

Bartók’s early compositions were published by Rózsavölgyi as well as Rozsnyai in Budapest. The first contract with Universal Edition, whose director Emil Hertzka was also of Hungarian birth, was concluded in 1918. That is how Bartók’s only opera, Bluebeard’s Castle became part of the UE catalogue. For many years – until the fascist takeover and Bartók’s emigration to the United States – his works appeared in Vienna.

Hertzka’s name had first cropped up in Bartók’s correspondence with his family as early as 1901. The nineteen-year-old composer reported to his mother of his efforts to secure private lessons with a view to earning some money. Dr Hertzka apparently advised him not to take on more than ten or twelve pupils, so as not to jeopardize his studies.

The next time Hertzka’s name was mentioned in his correspondence was 1918: Bartók’s first wife, Márta Ziegler, wrote to her mother-in-law:

“And now, mark my words, all of you: Universal-Edition has got in touch with B. They want to publish all of his works and conclude a contract for a period of 6 to 10 years. (B. will probably decide in favour of 10 years). They will commit to bringing out 4 compositions per year. Beyond that, they would like to take over the complete oeuvre, also the pieces published by Rózsavölgyi and Rozsnyai. The question of royalties is to be discussed at a later date. I shall be writing you about it once the contract has been signed. B. is over the moon; that suffices, doesn’t it? For this means not only that all his works which have not been published in the past will appear in print (since B. never composes more than 2 pieces a year, the other 2 will be taken from among the existing ones) but also that Universal will be doing a great deal of publicity for the stage works so as to promote the sales of the scores. Hertzka has had sufficient time to make up his mind since the pantomime which apparently scared him no end. He is a good businessman; he never takes his decisions on the spur of the moment.”

By pantomime Mrs Bartók meant The Wooden Prince.

The fact that Emil Hertzka took promotion very seriously indeed can be deduced from a letter of Mrs Bartók’s written in 1920:

“Last week, we received a note from his publisher, Hertzka, from New York: he says he has approached quite a number of pianists to interest them in the works and they want to play them too. ‘Bear Dance’ has been printed anew in America.”

In 1923, Bartók informed his mother that Hertzka was planning a whole week of performances in Vienna, along the lines of a concert series in Berlin – but Hertzka meant to do a better job of it.

In 1928, Hertzka visited Bartók in Budapest and expressed satisfaction with the composer’s new flat. “We discussed some topics of a business nature and talked also of my recent works. I was, you see, once again quite diligent during the summer: have written a piece for violin and piano of some twelve minutes [Bartók was referring to the Rhapsody No 1], this is on a smaller scale. The larger composition is a new string quartet [No 4] which involved rather a great deal of work. It is nearly finished. Ditta and I have tried to play the first movement on two pianos, i.e. we have worked at it quite hard, because it is pretty demanding.”

Bartók visited Universal Edition in 1930 and met Hertzka who had recently returned from the United States. He also met several employees of the firm as well as Rudolf S. Hoffmann, translator of the 20 Hungarian Folksongs. He was also given some scores to correct which he dealt with the very same evening.

The only hint that the relationship between Bartók and Hertzka was not always cloudless is to be found in a letter of 1931, written by the composer to his mother. He says contact between them reached a dead end, but he was nevertheless prepared to prolong the contract. Other sources indicate that Bartók was not always happy with the service provided by his publisher. For instance, he deplored the fact that the score of the Piano Concerto No. 1 was lithographed rather than engraved and no pocket score was published. Of course, these were hard times what with the stock market crash of 1929 and its aftermath: UE had to economise.

Those were nevertheless halcyon days for Bartók which came to an end with Emil Hertzka’s death in 1932 and Austria’s annexation by Nazi Germany in 1938. Bartók was desperate: the political events upset him and he was of course worried about the fate of his works with the “aryanised” UE. The firm waived the prolongation of the contract in 1939 and Bartók joined Boosey [&] Hawkes.

It marked the end of an important chapter in the history of Universal Edition as well as in the life of Béla Bartók. The composer died in the United States before contact could have been re-established after the end of World War II.