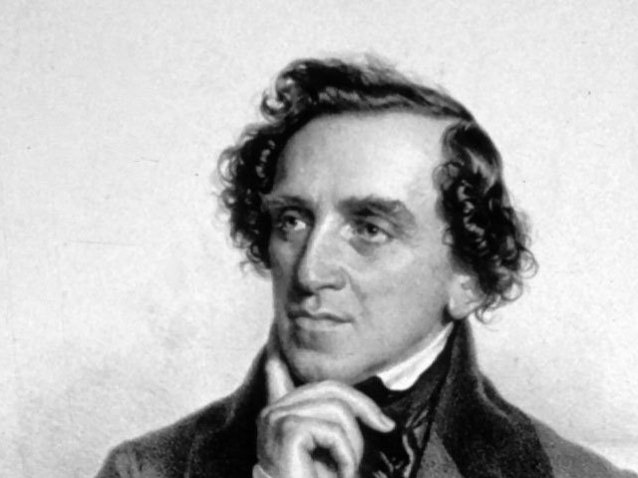

Giacomo Meyerbeer

*5 September 1791

†2 May 1864

Works by Giacomo Meyerbeer

Biography

Giacomo Meyerbeer’s forgotten treasures

Edited by musicians for musicians

Director: Andrea Chudak

Sheet music: Max Doehlemann

Giacomo Meyerbeer was born on September 5, 1791, the son of Amalie and Jacob Herz Beer in Tasdorf near Berlin; his birth name was Meyer Beer. Growing up in an affluent and socially well-connected Jewish family, he received a profound musical education from the most distinguished teachers of the day. He studied piano with Muzio Clementi and composition with Abbé Vogler and Carl Friedrich Zelter, the director of the Berliner Singakademie. Carl Maria von Weber was also a student of Vogler’s, and the two became lifelong friends.

In 1816, Meyerbeer took Antonio Salieri’s advice to go to Italy to immerse himself in opera. There, he took the name Giacomo Meyerbeer. He was particularly influenced by Gioachino Rossini’s operatic oeuvre, yet he soon developed his signature style: the extraordinary richness of his ideas, their dramatic quality, harmonic color, and wit are hallmarks even of these early compositions. Leading opera houses began to stage his works. His last Italian opera Il crociato in Egitto premiered at the Teatro la Fenice in Venice in 1824, bringing him international attention.

In 1830, he went to Paris, where he gained broad recognition as “Master of the Grand Opéra”; his series of successes included Robert le diable (1831), Les Huguenots (1836), and Le Prophète (1849). Meyerbeer’s operatic oeuvre was pioneering and epochal. Influenced by the societal upheavals of the day and taking a stand on the issues, it is nonetheless universal and timeless. Meyerbeer used his vast capabilities of musical expression to open up new ways of thinking about opera. He introduced new orchestral instruments and worked with innovative stagecraft techniques. Besides his operas, he also composed orchestral works, secular and religious cantatas, concert arias, and choral works, as well as vocal and instrumental chamber music, lieder, romances, ballads, and works for solo piano.

In 1842, he was appointed Kapellmeister of the Prussian court, as Gaspare Spontini’s successor, and Generalmusikdirektor of the Royal Court Opera House in Berlin. He lived in Paris again from 1846 on, devoting himself entirely to composing. Meyerbeer died there on May 2, 1864; his body was brought to Berlin and buried at the Jewish cemetery on Schönhauser Allee a week after his death.

Despite all his successes that made him one of Europe’s best-known composers during his lifetime, Meyerbeer was always also confronted with an unusually large number of detractors and enemies. As a composer of vocal works in various languages, a cosmopolitan who moved easily across Europe, Meyerbeer did not fit in with the emerging mentalities of Romantic nationalism – the leitmotif of the Romantic period was more a language of emotion founded in national schools and regionalisms and with aspirations of identity-based belonging. In contrast, Meyerbeer was a polyglot citizen of the world, a universalist in the spirit of enlightened Berlin Reform Judaism. Because of the dogged, overblown criticism of Meyerbeer with decidedly antisemitic undertones, he was gradually edged out of the public consciousness after his death. The Wagnerians played a particular role here, but also music writers such as Hugo Wolf. This got to the point that many of his works, widely printed during his lifetime, disappeared from the canon and the libraries – until they were eventually considered lost. Additional material was destroyed or scattered during the Nazi period.

About the music

Meyerbeer’s major operas never disappeared entirely from the repertoire and have seen an encouraging renaissance in recent years. Today’s audiences are still entirely unfamiliar with his piano works, cantatas, orchestral pieces, concert arias, choral works, lieder, and quite a number of other compositions.

All of Meyerbeer’s music is distinguished by his consummate mastery and detailed elaboration of the musical forms, be they dramatic or lyrical, for symphony orchestras or chamber music ensembles. One of his most important means of expression is the human voice, but he is by no means purely a composer of vocal works. Meyerbeer’s sound features the entire range of expression of the early Romantic period – yet without its at times petit-bourgeois and regional-national orientation. His music is full of timeless freshness and depth. And we consider Meyerbeer to be as topical as ever as an outstanding musical representative of a polyglot, pan-European spirit.

Many of his smaller works were composed for special occasions, for example court festivities. In his vocal works, apart from his commissioned pieces, the diversity of what Meyerbeer considered worthy of being set to music is striking, ranging from witty or dramatic lyrics about love to literary or religious subjects to Jewish liturgy. Unfortunately, musicology has contributed little to date to accessing this multi-faceted oeuvre anew or to locating lost works.

Soprano Andrea Chudak and a dedicated group of aficionados seek to contribute to filling this gap as best we can. We have painstakingly researched archives and collections in Germany, England, and Israel and rediscovered numerous lost works. We are proud to make this musical treasure trove available to the public in a new edition.

We call our series “Giacomo Meyerbeer’s forgotten treasures.” We are not aiming to publish an academic edition, but it goes without saying that we carefully compare various versions and correct errors in the old prints. A team of musicologists and musicians is available to help us with detailed questions. As practicing musicians, our main goal is to help make these outstanding compositions available once again so that they can be performed, so we chose “Edited by musicians for musicians” as the subtitle of our series.

We thank Universal Edition for the opportunity, and especially for the liberating artistic space that Scodo provides. The new editions of Meyerbeer’s works are a collaboration of Andrea Chudak and Berlin-based composer Max Doehlemann, who prepares the scores. We extend our warmest thanks to Thomas Kliche, Berlin.