Works by Hanns Eisler

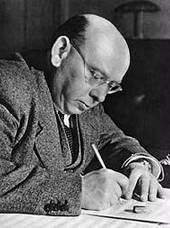

Biography

According to Theodor W. Adorno, Hanns Eisler is "the real representative of the young generation of Schönberg’s pupils and, moreover, one of the most talented of all young composers." Son of philosopher Rudolf Eisler, Hanns was born on 6 July 1898 in Leipzig and moved as a child to Vienna. From 1919 to 1923 he was a pupil of Schönberg.

Eisler’s compositional voice was already discernible in his prize-winning Piano Sonata op. 1 and in the many-facetted Piano Pieces op. 3. From 1925 onwards, in Berlin, it manifested itself clearly in the unmistakable coutours of his oeuvre. In his song cycle Zeitungs-Ausschnitte op. 11(Newspaper clippings) composed there, he combined the aphoristic technique of the Second Viennese School with themes of from everyday life in the metropolis. Eisler composed works in almost all orchestrations and in a number which by far surpasses the creative output of two other Schöberg pupils, Alban Berg and Anton Webern.

Like Paul Hindemith and Kurt Weill, Eisler burst the boundaries of traditional music genres. He composed for areas outside of the concert halls and achieved wide recognition with pieces for new purposes. Among these were pieces for experimental film and radio, for workers’ choruses, for theater and cabaret, and also for pedagogical purposes, to which he dedicated a part of his energies throughout his lifetime. Eisler’s new impulses for performance practice as well as his Dialectic of Musical Material characterize his musicological and pedagogical Wirken. In this sense his work as composer and politically aware contemporary were relfected theoretically and philosophically in his vast umfangreich writings. Since his youth in Vienna, he continued this part of his work: in Berlin, New York and Los Angeles. In post-war Berlin (East Germany), Hanns Eisler conducted a master class for composition at the German Academy of the Arts and was professor at the Musikhochschule that since 1964 has borne his name.

In the foreground of Eisler’s compositions are his numerous vocal works. They range from large song cycles (like the Hollywood Song Book, comparable to the song cycles of Schubert, Schumann, Brahms, and Wolf), to cabaret numbers, to popular songs for the masses; from cantatas, choruses, Lehrstücke (political didactic pieces), large incidental works to requiem and vocal symphony. In the instrumental music, the diversity is also overwhelming. The piano sonata or string quartett is more the exception than the rule in the forms typical to Eisler, in which art and functionalism are combined.

Music critic H. H. Stuckenschmidt made the following judgement: "Of all composers alive today, he is among the most effective, decisive and clear; for with his music he successfully responds to the situation of the present." Eisler was not only composer, he was also intellectual partner and friend of Theodor W. Adorno, Thomas Mann, Lion Feuchtwanger, Charlie Chaplin, Ernst Bloch, and Wolf Biermann – a witness of his century.

An unprecedented musical-literary symbiosis connects Eisler to Bertolt Brecht, a beginning in 1930 and not ending until Brecht’s death in 1956. With no other composer did Brecht maintain such intense collaboration over so prolonged a period of time. Large works for chorus like Die Massnahme, cantatas like Die Mutter, films like Kuhle Wampe and Hangmen Also Die (director: Fritz Lang), as well as innumerable songs and incidental music (like Schweyk im Zweiten Weltkrieg) were fruits of this collaboration.

Eisler was a vociferous critic of the Nazis and accordingly was forced to flee Berlin into exile in 1933: first to Europe, later to the USA. From abroad, he took part in the organzation of the resistance; he expressed his standpoint in writings and in musical works, from the smallest piano pieces and songs to the large-scale German Symphony. He countered the Nazis’ cultural policy with his belief in modernism and in Schönberg’s twelve-tone technique.

In 1938 Eisler was professor in New York, in 1942 in Los Angeles where, together with Adorno and Brecht, he sought new possibilities for film music in theoretical, as well as practical terms. Directors like Joris Ivens, Jean Renoir, Joseph Losey, Fritz Lang, and Alain Resnais were his partners in developing an alternative esthetic for Hollywood’s film music. Moreover, during his American exile many of his most important songs, works for orchestera, and chamber music were written. Like Joseph Losey and Charlie Chaplin, Eisler was forced [by the House Unamerican Activities Committee; editor's note] to leave the USA. As farewell, prominent American colleagues, among them Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein, honored him with a farewell concert in New York.

In 1950 Eisler returned to Berlin, passing through Vienna. His enthusiasm for a "new Germany" (East Germany), however, quickly evaporated. A communist party campaign against his Faustus opera project lamed his creative powers. In 1954 his declaration favoring Schönberg's twelve-tone technique aroused official resistance. The honors Eisler received as composer of the German Democratic Republic's national anthem could not conceal the fact that some of his principal works were hardly performed. The Ernste Gesänge (Serious songs) composed shortly before his death are a sobering summation of his experiences.

Hanns Eisler’s name is intertwined with the contradictions of a turbulent century. Only since the Germany's reunification does a real chance exist to make an impartial and thorough assessment of this richly productive composer.

Albrecht Dümling