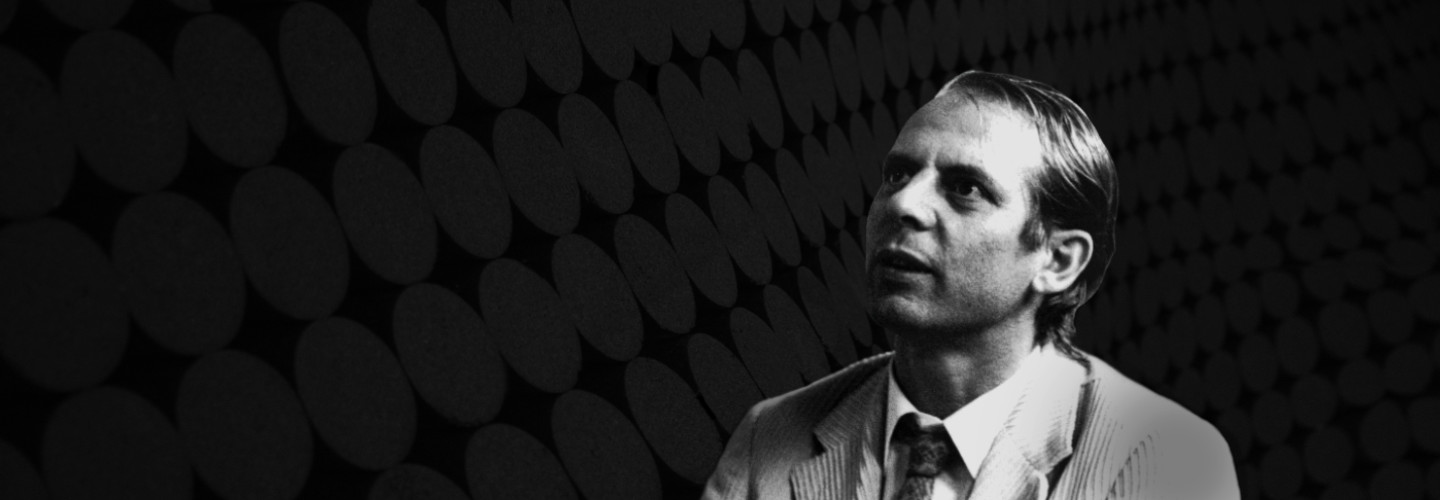

Karlheinz Stockhausen

*22 August 1928

†5 December 2007

Works by Karlheinz Stockhausen

Biography

Born in 1928, Karlheinz Stockhausen was eleven at the start of World War II and was old enough to experience the ensuing years with the consciousness of a premature child and adolescent. That consciousness was heightened by tragedies in his family which must have left an indelible mark on his mind. Here is how he himself described it:

“Both parents came from a rural background. The mother, bearing three children in just three years and living in utter poverty, began suffering deep depressions and was committed to a mental hospital, where she was officially killed in 1941. The father managed for a few years with housekeepers, marrying one of them, who bore him two more children; he then volunteered for the army in 1939, dying a ‘heroic death’ somewhere in Hungary”.

“Stockhausen attended school, became a field hand on a farm, learning Latin at night and was accepted at the State Academy of Music in Cologne in 1947 for Hans-Otto Schmidt-Neuhaus’ piano class. Studied music education from 1948 to 1951, received his teacher’s licence summa cum laude, all the while played in Cologne bars almost every night, as well as for dancing classes, toured as an improvisational musician with the magician Adrion for a year, directed an amateur operetta theatre, spent his vacations working in a factory, or as a parking lot attendant, or guarding homes of occupation troops. Prayed a lot.”

Although written in the third personal singular, that fragment of an autobiography was written by the composer. It has been quoted partly for the dates listed there. For it is a veritable miracle that as early as 1951, with the background he had, Stockhausen should have composed Kreuzspiel for oboe, bass clarinet, piano, and three percussionists – a work that was to become an integral part of the international repertoire. He was only 23 years old. And in the years that followed, there emerged further compositions which were to serve as examples for other composers to follow, to study, to take their cue from: Spiel for orchestra 1952, Punkte for orchestra 1952/1962, Kontra-Punkte for ten instruments (1952/1953), Piano Pieces 1-4(1952/1953), and most amazingly of all, Gruppen (1955/1957) for three orchestras. A genius was at work, one who in the years following World War II when composers were determined to break with the past and start anew, lit a torch and showed the way to generations. The torch was not to go out for decades, with one masterpiece following close on the heels of another: in 1953, at the age of 25, Stockhausen composed Studie I for sinus tones - the first purely electronic music. It was followed up by Gesang der Jünglinge, electronic music with a boy’s voice in 1955/1957. There came Zyklus (1959), Refrain in the same year, both versions of Kontakte also in 1959 and so it continued in the sixties (Hymnen and Stimmung among many other important contributions to new music).

Back in 1951, there came to an encounter which was to prove of decisive significance for the 23-year-old composer’s development. This is how he described it:

“In Darmstadt, in 1951, at the ‘Summer Courses for New Music’, a French music critic played a record of Messiaen’s Quatre études de rythme. One of the etudes is entitled Mode de valeurs et d’intensités. I asked him there and then to play the piece again and again and a whole new world opened up before me – an inner world – in listening to this ‘point music’, this ‘star music’, as I called it at the time. After the Darmstadt Summer Courses were over, I returned to Cologne and told a music critic of this experience. He asked: ‘What does this music sound like?’ And I repeated: ‘It sounds like the stars in the sky.’

At these Summer Courses I also met a Belgian pupil of Messiaen’s, Goeyvaerts, and he explained how Messiaen had composed the piece. It clarified many things for me, because I had written twelve-tone music before but it had never occurred to me that rhythm could be just as non-periodic as pitches could be non-tonal or that the intensities of the pitches could also be so different.

Later on when I heard it again, the piece did not have such a strong effect on me. However, it was thanks to that experience that four months later, in January 1952, I moved to Paris because I was determined to study with Messiaen. I attended his courses on aesthetics and rhythm for a whole year”.

The throwaway statement in the autobiography “I prayed a lot” and the association of Messiaen’s “point music” with the stars shows an early predilection for the transcendental. It was an undercurrent in works with a great deal of music-theoretical thinking determining the parameters – like in Stimmung, where the title refers as much to just intonation with the singers singing the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 7th and 9th overtones of the deep B flat as it does to atmosphere or aura. “Surely, ‘Stimmung’ is meditative music. Time has been suspended. One listens to the heart of the sound, of the harmonic spectrum, of a vowel, to the inner heart.”

The same is true of Mantra for two pianists where in addition to complex theoretical

considerations and the use of 'ringmodulation' which enabled Stockhausen to create a new system of harmonic relationships, there was also a higher goal: the composer considered the unified construction of “Mantra” to be a musical miniature of the unified macro-structure of the universe, in addition to the projection into the acoustic time field of the unified micro-structure of the harmonic oscillations in the tone itself.´

The transcendental aspect was to acquire growing significance in Stockhausen’s thinking and it manifested itself in compositions with which Universal Edition was no longer associated.

It had been Alfred Schlee, a long-time director of UE, who after a concert went up to Stockhausen and announced to him “I am your publisher”. And it ended in the late 1960’s when the composer decided to publish his music himself.

Now that Stockhausen is no longer with us, time – which he succeeded in suspending in so many of his compositions – will assume the role of Judge to decide on the future of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s oeuvre. While the Judge is deliberating, many of the pieces which he assigned over half a century ago to Universal Edition, are being played as a matter of course.

About the music

Compositional metamorphoses

There are certain labels which – despite an inevitable tendency towards exaggeration – can nevertheless serve as preliminary indicators of a composer’s orientation. One such label is the phrase ‘conservative revolutionary’, used by Willi Reich to characterise Schoenberg. Among composers who left a significant mark on the second half of the twentieth century, this same description may most readily be applied to Karlheinz Stockhausen. The innovations for which he was responsible are manifold and, to a large extent, familiar also to a wider audience:

- decisive contributions to the development of serialist musical thinking; exemplary compositions with their accompanying theoretical concepts;

- the development of a form of electronic music derived from serialist thinking;

- attempts to emancipate the performer and to compose open forms susceptible to variant interpretations;

- ideas of a more inclusive musical language, which might serve as a bridge between traditional and novel structures, forms and styles.

Yet at the same time, right from the start of his career Stockhausen repeatedly tried to bridge tradition and innovation, and on a number of occasions had to defend himself against the charge of aesthetic and ideological conservatism. Things in Stockhausen’s development that, for many, might seem difficult to reconcile or even contradictory cannot simply be explained by the later changes of direction of the former avant-garde radical. In terms of the overall progress of his compositional development they make their appearance relatively early on.

The Stockhausen of the early 1950s is generally perceived as the radical representative of a ‘pointillist’, totally serialised style, surrounded by an atmosphere of scandal. Only shortly afterwards, however, he was already presenting himself as one of the first to attempt to replace the atomisation of early serial music by other compositional concepts. The radical anti-traditionalist who, as one of the pioneers of electronic music, for a time seemed to be contemplating the abandonment of instrumental music altogether, was already paying homage to instrumental music again in 1954, the year in which his first electronic works received their premières.

After starting out as a constructivist influenced by Olivier Messiaen and Karel Goeyvaerts, after studying the emancipation of noise in Edgard Varèse and the early music of John Cage, and after an intense theoretical/analytical involvement with the works of Anton Webern, Stockhausen began to establish a reputation for himself with his own original ideas. With instrumental works, whose serial rigour was mitigated by interpretative freedoms – which even today are frequently understood as a response to what were then the most novel experimental tendencies in the music of Cage and his pupils. With spatial music – with the result that Gruppen for three orchestras (1955–57) in particular inspired other composers such as Henri Pousseur and Pierre Boulez to produce spatially conceived compositions. With innovative concepts regarding the compositional integration of music and language – in which respect what Stockhausen attempted in Gesang der Jünglinge (1955–56) may, on the one hand, be understood as an alternative to Boulez’s Le Marteau sans maître (1953–1955/57) and Luigi Nono’s Il canto sospeso (1955–56), while on the other hand – considered as electro-acoustic music – as exerting influences with regard to compositional technique that went beyond these pieces, as for example may be detected in Luciano Berio’s Thema (Omaggio a Joyce) of 1958. With various examples of aleatoric music – for example in Klavierstück 11 (1956), whose modular, variable form was for a while prized by Cage, but also criticised by a number of opponents and even supporters of the composer. While in his theoretical works of the 1950s, which are closely bound up with his compositional practice, Stockhausen established himself as one of the most important exponents of serial music and, indeed, of all new music since 1945.

Already in Kontake, completed in 1960, a composition that takes a particularly bold leap forward in the emancipation of noise, one detects that tendencies had developed in Stockhausen’s work which were not easy to reconcile with one another. The technique of electronic sound production – irrevocably fixed, highly involved technically and novel in terms of the sounding result – did not, at the time, permit the connections with spontaneous and variable instrumental performance Stockhausen had initially envisaged, nor the integration of familiar instrumental timbres with the electronic sound continuum which he had planned for this piece. This drove Stockhausen’s development towards a crucial borderline – and the alternative conceptions which he developed from this time onwards occasioned even Dieter Schnebel (a notable supporter of the Stockhausen of the 1950s) to make the distancing comment that Stockhausen’s music had ‘become different since 1960’.

The highly differentiated, serially organised rhythmic constructions on which Stockhausen had based his Gruppen for three orchestras were already to be abandoned in the subsequent spatial works for voices and instruments: Carré for four orchestras and four choirs (1959–60) is an expansive, meditative work in which the durations are notated only as approximate proportions. This emancipation from fixed conceptions of form also continues in the complex, variable ‘moment forms’ of the 1960s – in the formal sections of the cantata Momente (begun in 1962), which may be arranged in various ways and nested one inside the other, or the excessively ‘noise-like’ Mikrophonie I for tam-tam with live electronic manipulation (1963).

In general, however, it may be observed that in the 1960s Stockhausen – above all in his instrumental music – increasingly relaxed the abstract rigour of his earlier work. Schnebel complained that ‘private traits’ and ‘the lure of the monumental’ asserted themselves in Stockhausen’s music from this time onwards, from which he drew an extremely critical conclusion: ‘A sense of high-flown thoughts and of the all-embracing – as well as its correlative, the concentration on the inner world – emerges in Stockhausen’s later work. This reflects a specific ideological consciousness – that of domination.’

But this ideological criticism – coloured as it is by overtones of personal attack – does not suffice to explain why Stockhausen’s music underwent such dramatic changes as early as the 1960s. Why – one has to ask oneself – did Stockhausen return to minutely crafted tape compositions such as Telemusik (1966) and Hymnen (1966–67), only to turn afterwards increasingly to laconic ‘conceptual art’ pieces for his live electronic ensemble? Why did he create scores for extended pieces whose notation was drastically reduced to sparse symbols or verbal texts? Why – it must also be asked – did Stockhausen then turn his back so swiftly on the extreme manifestations of this type of composition, e.g. Aus den sieben Tagen (1968), and return to fixed scores, indeed to traditional notation – particularly remarkably after his 1970 live electronic work for two pianists Mantra?

When one examines Stockhausen’s development, one must engage with the fact that positions already attained are subjected to radical questioning before the search for a synthesis of apparently irreconcilable opposites can begin. It would be rash, therefore, to try to categorise Stockhausen’s manifold attempts at compositional synthesis according to similar labels derived from ideological criticism – whether it is a matter of synthesising semantically organised sound and speech materials with electronic sounds, or determined music with music that permits interpretative freedom; instrumental with electronic music, or more abstract music with music of more semantic character; or purely aural music with music synaesthetically integrated. In the 1960s and 1970s it became clear that the search for synthesis in Stockhausen’s music was extending further: a synthesis between ‘tonal’ and ‘non-tonal’ compositional techniques was also being attempted. What was particularly remarkable about these attempts at synthesis was that tone rows, which had remained concealed in the complex stratifications of the earlier works, after Mantra (1970) suddenly made their appearance as readily recognisable, easily singable melodic forms. Stockhausen’s development had led ‘from the row to the melody’, from atonal structures to wholly thematic forms that, once again, possessed a strongly tonal character; from a continuation of Webern’s total serialism to a resurrection of thematic craft in the spirit of mid-period Beethoven or Bach’s polyphony.

The obvious simplification of compositional technique and audible thematic connections to which this gave rise have often been criticised – not least, once again, by those who prefer the older works with their more complex structures. By no means the least provocation for rebarbative attacks in this critical discussion was the fact that it was precisely these melodic works which Stockhausen was particularly insistent on presenting as strictly constructed programme music, as composed allegories. Thus the programme note for Mantra already proclaims a synthesis between a conception of the work typical of ‘absolute music’ (ideational unity between the structure of details and larger formal connections) and its programmatic, symbolic meaning as cosmic allegory: "The integrated construction of 'Mantra' is a miniaturised musical replica of the integrated macrostructure of the cosmos, and at the same time a magnification into the realm of acoustic time of the integrated microstructures of the harmonic oscillations within sound itself."

In Inori (1973–74), the extra-musical intentions behind the developments of different parameters expressed instrumentally in the orchestral part are given explicit visual expression: as gestures of prayer, the organisation of whose various dimensions parallels that of the music. The four main melodies of the expansively conceived Sirius for electronic sounds and four soloists (1975–77) are explained in the sung texts as polysemic musical symbols – for example as symbols for the four points of the compass, the four elements of the ancients, four times of day, four seasons, four stages of biological growth.

Licht – the music-theatrical cycle begun in 1977 and intended for seven performance spaces – is conceived as an allegory of the seven days of the week, in which the three principal melodies dominating the whole cycle are to be understood as musical symbols for the principal characters Michael, Eva and Lucifer. Stockhausen– who, in his readiness to offer explicit, aesthetically and analytically defensive self-commentary certainly has much in common with Richard Wagner – attempts here to undertake a summa of his previous compositional activity – already spanning more than a quarter century – in the shape of a monumental work calculated to require around twenty five years’ compositional elaboration: a second stocktaking, begun a decade after the first performance of Hymnen, which was intended to perform a similar function for its own time. However, while the dedications of Hymnen point to an engagement with alternative aesthetic positions in modern music (the first ‘region’ of the piece, developed with formal rigour, was dedicated to Pierre Boulez; the second – with its blunt political references – to Henri Pousseur; the third – colourful and collage-like – to John Cage; and the fourth – richly differentiated in terms of timbre – to Luciano Berio), the melodic constellations in Licht are to be understood in the first instance as a consequence of Stockhausen’s own (compositional and aesthetic) development in the 1970s. Whereas the older thematic works of the 1970s were organised monothematically, the ‘superformula’ imposed on the three melodies of Licht is intended as a basis for music containing a multitude of themes and aesthetic perspectives. Thus a compositional development that took Webern as its starting point ended up developing into an orientation towards Bach in the spirit of Wagner.

Rudolph Frisius

Translation by Peter Burt