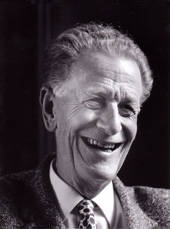

Frank Martin

In terra pax

Short instrumentation: 2 2 2 2 - 4 2 3 1 - timp, perc(5), cel, pno(2), str

Duration: 43'

Übersetzer: Romana Segantini, John H. Davies, Vittorio Gui

Choir: SATB, girls choir ad lib.

Solos:

soprano

alto

tenor

bass

Instrumentation details:

1st flute

2nd flute

1st oboe

2nd oboe

1st clarinet in Bb

2nd clarinet in Bb

1st bassoon

2nd bassoon

1,2th horn in F(2)

3,4th horn in F(2)

1st trumpet in C

2nd trumpet in C

1st trombone

2nd trombone

3rd trombone

tuba

timpani

percussion(5)

1st piano

2nd piano

celesta

violin I

violin II

viola

violoncello

double bass

Martin - In terra pax for 5 vocal soloists, 2 mixed choirs and orchestra

Printed/Digital

Translation, reprints and more

Frank Martin

In terra paxOrchestration: for 5 vocal soloists, 2 mixed choirs and orchestra

Type: Klavierauszug

Language: Französisch

Frank Martin

Martin: In terra paxOrchestration: für 5 Vokalsolisten, 2 gemischte Chöre und Orchester

Type: Dirigierpartitur

Language: Deutsch | Französisch

Frank Martin

Martin: In terra pax for 5 vocal soloists, 2 mixed choirs (SATB) and orchestraOrchestration: for 5 vocal soloists, 2 mixed choirs (SATB) and orchestra

Type: Klavierauszug

Language: Deutsch | Französisch

Frank Martin

Martin: In terra pax for 5 vocal soloists, 2 mixed choirs (SATB) and orchestraOrchestration: for 5 vocal soloists, 2 mixed choirs (SATB) and orchestra

Type: Chorpartitur

Language: Englisch | Italienisch

Frank Martin

Martin: In terra pax for 5 vocal soloists, 2 mixed choirs (SATB) and orchestraOrchestration: for 5 vocal soloists, 2 mixed choirs (SATB) and orchestra

Type: Chorpartitur

Language: Deutsch | Französisch

Sample pages

Audio preview

Work introduction

It was 1944, and the war continued; Mr. René Dovaz, director of Radio Geneva, asked me to write a piece which would be broadcast immediately after the cessation of hostilities was proclaimed. Naturally, it could only be a religious work. I complied with his request gladly, but perhaps even more with anxiety; I was obliged to confront the images of war and peace and the expression of all the suffering and joy, but also the peoples’ emotions at the moment of that enormous relief, the flash of exhilaration that the wonderful news would unleash. Even more, it was utterly impossible to foresee the form that great event would take. Only one thing was certain; the hostilities would cease. So, in the summer of 1944, I was to evoke the overflowing joy of the longed-for moment amidst the anxiety for the future, the immeasurable sorrow, everywhere the ravages of the war.

I resolved to construct my work out of four sections and to look for suitable texts in the Bible. The first part deals with war itself, which the prophets considered was the consequence of God’s wrath. The second proclaims liberation, the outbreak of joy of a people feeling new hope and life. The third section introduces an entirely new thought: the notion of Christ. It is largely taken from the prophecies of Isaiah, who describes the servant of eternal God as one scorned, as a lamb being led to the slaughter. This text contains answers in the form of Christ’s words concerning the necessity of forgiveness and love, conditions for a true peace. Then the chorus ends with the Lord’s Prayer. The fourth and final part evokes the new Heaven and the new Earth, freed from all worldly matters, where all tears will be dried, where there will be no cries or suffering. It ends with the mystic averment “Holy, holy, holy is God the Lord.”

While composing the oratorio, I do not believe I ever had any illusions about the nature of peace that would follow the war’s end; but that absence of illusion could not restrain me from attempting to express the transition from deepest despair to hope for a shining future. And that meant that, in the words of Christ, I testified to the absolute requirement of forgiveness, without which true peace is inconceivable. But that requirement is so great that its universal acknowledgement on earth is unimaginable without the miracle of complete transformation of human thought and feeling. Therefore, for us, true peace can only be a hope, a determination, a faith, a bridge to an uncertain future – but a future we must imagine, even if we cannot believe in its material and earthly realisation.

Thus, I believed, could the end of the hostilities be celebrated, apart from the completely natural and spontaneous joyful utterances of thousands thronging the streets, their flags waving. To put it one way, the piece is a work for a specific occasion; but I myself have never considered it so. The complexities raised by war and peace are eternal; military wars are not the only kind – and is peace not a constant longing of our souls?

Frank Martin