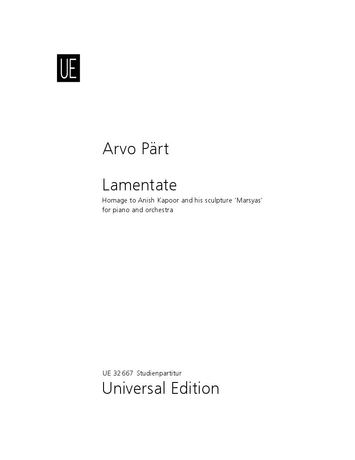

Arvo Pärt

Lamentate

Short instrumentation: 3 2 2 2 - 4 2 2 0 - timp, perc(4), str

Duration: 37'

Solos:

piano

Instrumentation details:

piccolo

1st flute

2nd flute

1st oboe

2nd oboe

1st clarinet in A

2nd clarinet in A

1st bassoon

2nd bassoon

1st horn in F

2nd horn in F

3rd horn in F

4th horn in F

1st trumpet in C

2nd trumpet in C

1st trombone

2nd trombone

timpani

percussion(4)

violin I

violin II

viola

violoncello

contrabass

Pärt - Lamentate for piano and orchestra

Printed/Digital

Translation, reprints and more

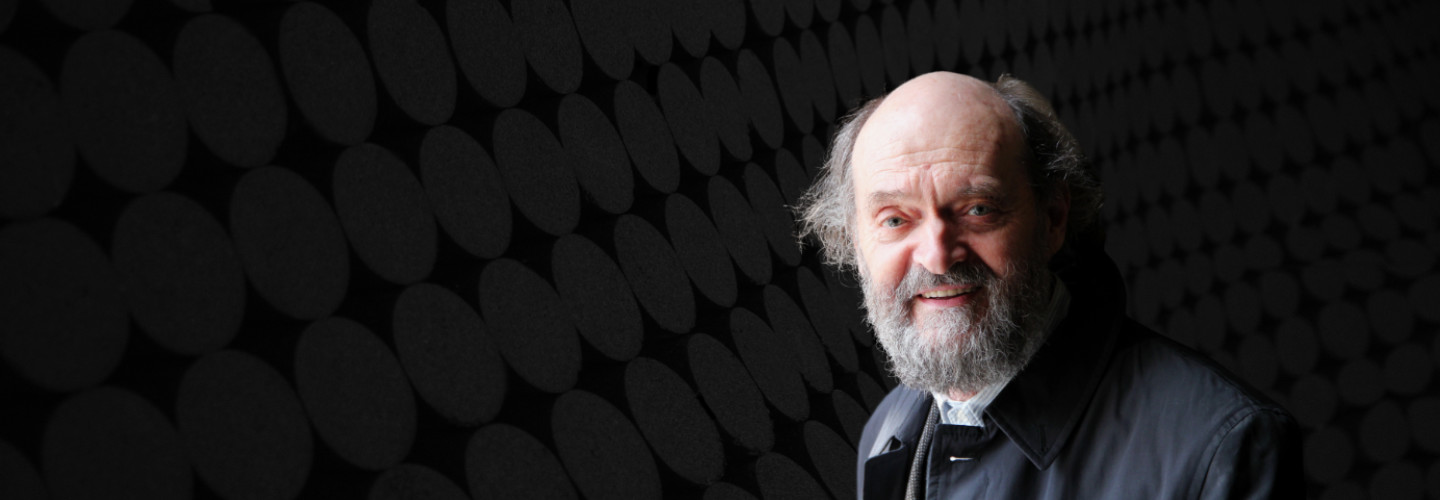

Arvo Pärt

Pärt: LamentateOrchestration: für Klavier und Orchester

Type: Solostimme(n) (Sonderanfertigung)

Arvo Pärt

Pärt: LamentateOrchestration: für Klavier und Orchester

Type: Dirigierpartitur (Sonderanfertigung)

Arvo Pärt

Pärt: LamentateOrchestration: für Klavier und Orchester

Type: Klavierauszug (Sonderanfertigung)

Arvo Pärt

Pärt: Lamentate for piano and orchestraOrchestration: for piano and orchestra

Type: Studienpartitur

Sample pages

Audio preview

Work introduction

When I first saw Marsyas by Anish Kapoor at the opening of the exhibition in the Turbine Hall, the impact that it had upon me was a powerful one. My first impression was that I, as a living being, was standing before my own body and was dead - as in a time-warp perspective, at once in the future and the present. Suddenly, I found myself put into a position in which my life appeared in a different light. And I was moved to ask myself just what I could still manage to accomplish in the time left to me.

Death and suffering are the themes that concern every person born into this world. The way in which the individual comes to terms with these issues (or fails to do so) determines his attitude towards life - whether consciously or unconsciously.

With its great size, Anish Kapoor’s sculpture shatters not only concepts of space, but also - in my view - concepts of time. The boundary between time and timelessness no longer seems so important.

This is the subject matter underlying my composition Lamentate. Accordingly, I have written a lamento - not for the dead, but for the living, who have to deal with these issues for themselves. A lamento for us, who don't have it easy dealing with the pain and hopelessness of this world.

In the presence of Anish Kapoor’s work, of which I have grown deeply fond, I sense a sort of completeness in its harmonious and so naturally flowing form, and in the rather paradox effect of floating lightness in spite of overwhelming dimensions. With its trumpet-like form, the Marsyas sculpture itself is suggestive of music. This larger-than-life 'trumpet-corpse' could be proclaiming the end of the world - as in a ‘tuba mirum’.

In his sculpture, Anish Kapoor has caught very well the tragic element of the Greek Marsyas myth. It was this tragic aspect that inspired me and provided the foundation for my composition. As in a relay race, I received the baton directly from the hands of the sculpture - and not from the legend itself. Hence, my composition is somewhat more indirectly based on the Marsyas myth, creating a sort of polyphonic counterpoint to the visual subject matter. My music has been conceived neither as an illustration nor as a decoration of the sculpture; it concentrates rather on its own, purely musical substance, in order to communicate the message which I associate with Anish Kapoor’s creation.

AboutLamentate

It is with great interest that I await the moment when all three objects d'art come together. Each of them was conceived and completed separate from the others. And yet, they do all have something in common. In my opinion, we three artists – Anish Kapoor, Peter Sellars and myself – have each based our respective works on the central idea of a “lament”, each in his own unique and individual way: Kapoor by a mythological approach, Sellars with allusions to current political developments, and I through music. As in a coalition whose very different members compliment each other without overlapping.

The Tate event brings these works together to form a unified whole.

It's the nature of the beast that the task of uniting these three works can only really be completed during the final phase. This period of genesis will be very intense and exciting indeed, with everyone involved being called upon to improvise and make new discoveries. It will be our job to link together three different fields of art and turn them into an event, while at the same time preserving every nuance, every facet of the individual works. The thing which is about to be created can only be presented in a constantly improvised and fluent form, and it’s absolutely conceivable that the two performances of the Tate Modern Event on February 7th and 8th might differ somewhat from one another, each becoming its own, one-of-a-kind happening.

Many of my creative decisions during the work’s composition were dictated by the unusual performance space and by the overall concept of the event. The Turbine Hall is not a concert hall with tried-and-true acoustics. We will much rather be venturing out into unexplored sonic territory. The hard part is that we'll only start to learn more during the rehearsal phase, when the musicians begin playing. How will the room answer us? How will the sculpture affect the acoustics? I have taken the incessant humming of the power plant in the building next door and made it part of my score – the whole tonal scope of the work revolves around this note. Additionally, I built into my composition opportunities for various placements of the wind instruments in the performance space. My special attention to this family of instruments has to do with the sculpture’s trumpet-like form.

Lamentate is music for piano solo and orchestra. With respect to its form, however, the composition cannot really be described as a typical piano concerto. I chose the piano to be the solo instrument because it fixes our attention on something that is ‘one’. This ‘one’ could be a person, or perhaps a first-person narrative. Just as the sculpture leaves the viewer with a light and floating impression in spite of its overwhelming size, the piano, as a large instrument, allowed me to create a sphere of intimacy and warmth that no longer seems anonymous or abstract. Overall, it could be said that my work is marked by two diametrically opposed moods. By way of slight exaggeration, I would characterize these two poles as being ‘brutal–overwhelming’ and ‘intimate–fragile’. The two characters are not simply placed opposite one another, much rather being left to develop themselves in a conflict that runs throughout the entire work.